In Ljubljana’s hilly pre-alpine landscape, forests are more than just a scenic backdrop. They play a crucial role in managing rainwater and reducing flood risks for downstream urban areas. Within the SpongeScapes project, scientists are taking a closer look at how different tree species influence rainfall, soil moisture, and the local water cycle in the Gradaščica catchment.

How Trees Interact with Rain

When it rains, not all water reaches the ground.

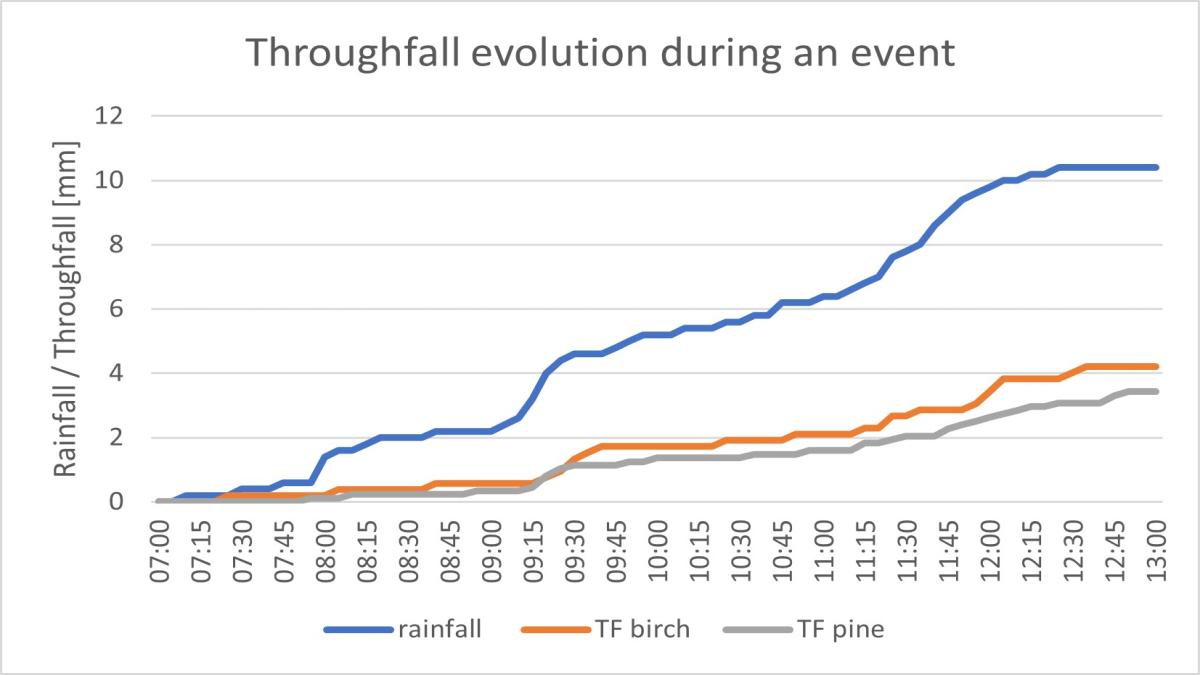

Some rain is caught by leaves, branches and trunks and can evaporate back into the air before ever touching the soil. This is called rainfall interception. The rain that does reach the ground, either by dripping through the canopy or flowing along branches and trunks, is known as throughfall and stemflow.

Trees also take up water from the soil through their roots and released it back into the air through their leaves – a process known as transpiration. Together, interception and transpiration help slow down runoff, store water temporarily, and regulate soil moisture.

Trees can also help reduce the impact of drought. They provide shade for the soil, meaning less water is lost through evaporation. Their roots also help to retain water in the area.

Measuring Trees in Action

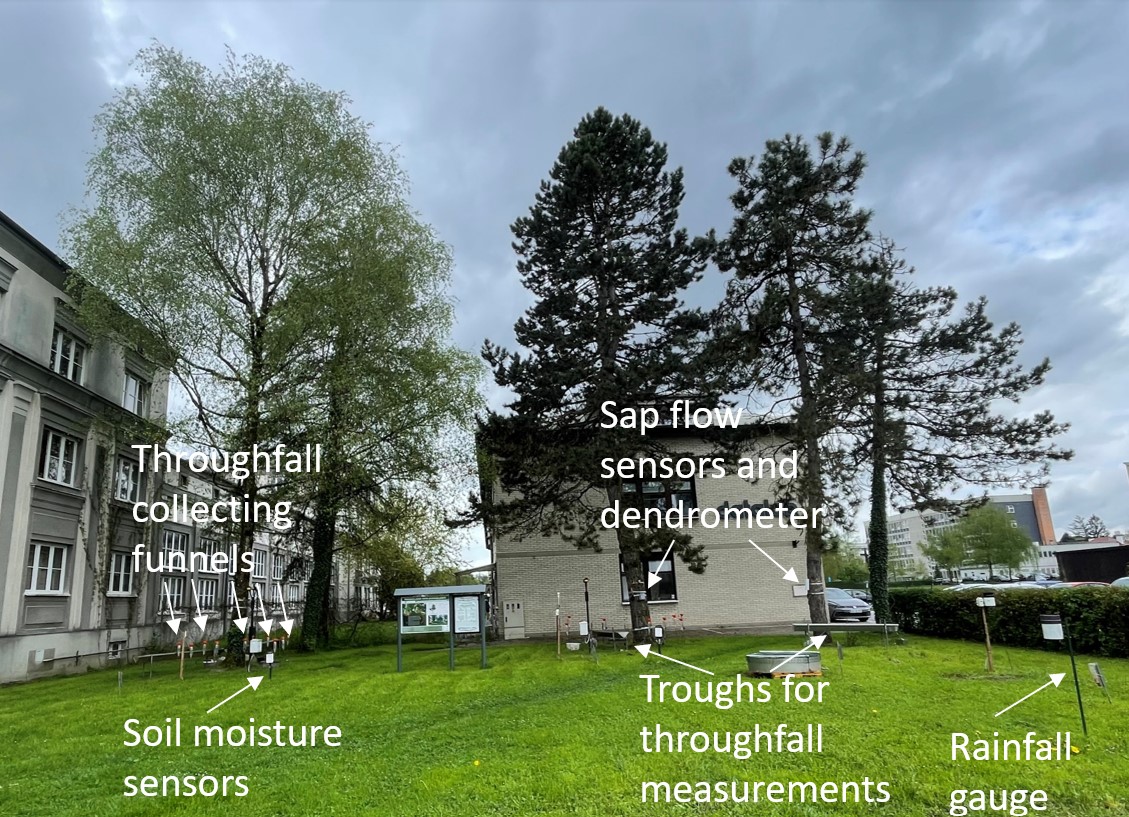

To better understand these processes, researchers from the University of Ljubljana have set up a detailed monitoring plot in a small urban park near the University, located within the Gradaščica catchment. The plot includes pine trees, birch trees, and an open area for comparison.

The team monitors:

- Rainfall in open areas using rain gauges and a nearby weather station

- Throughfall (rainfall under the trees) and stemflow using collectors placed under and on the trees

- Soil moisture at several depths, both in open areas and under trees

- Water movement inside trees (transpiration) using sap flow sensors

- Leaf area, which affects how much rain is intercepted and how much water is released back into the air

What the Data Shows So Far

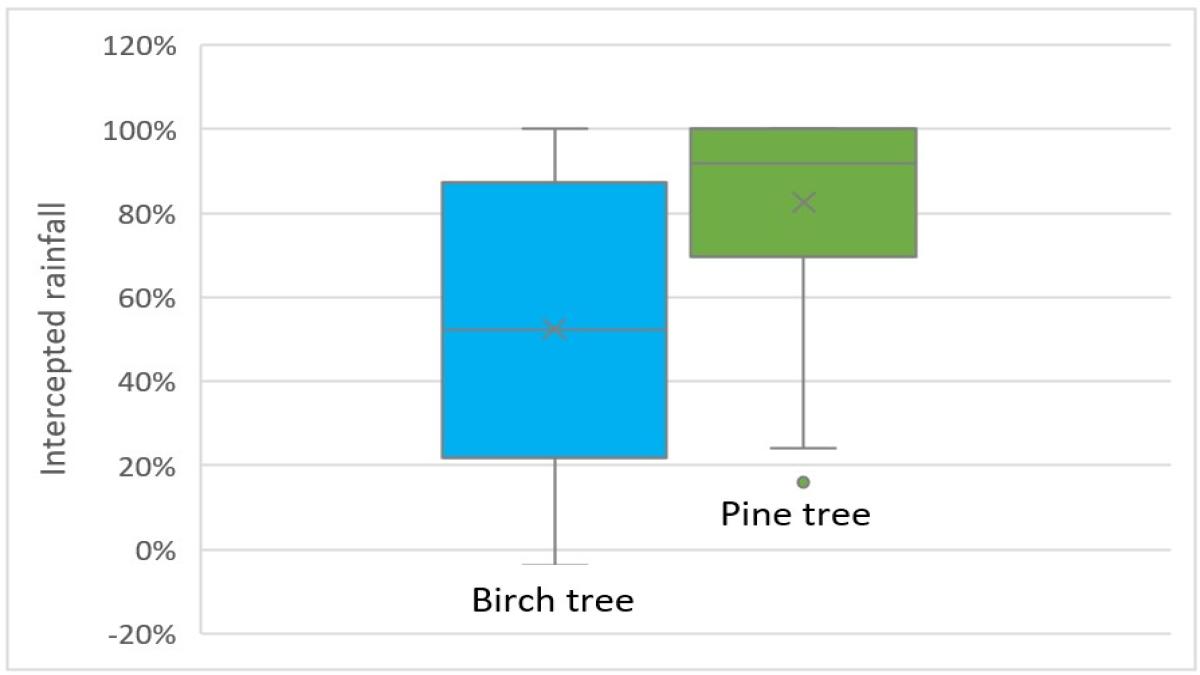

Early results show clear differences between tree species:

Pine trees intercept a large share of rainfall throughout the year – on average around 72%, with relatively small seasonal variation. Birch trees show much stronger seasonal differences. When leafless in winter, they intercept as little as 20% of rainfall, while in summer, with a full canopy, interception can reach up to 80%.

After rainfall, soil in open areas wets almost immediately. Under trees, the response is delayed by several hours. Soil beneath birch trees becomes moist faster, while soil under pine trees stays drier for longer, likely due to the effect of pine needles and resin.

Trees also behave differently when releasing water through their “transpiration”. During dry periods, pines gradually reduce the amount of water they release, while birches maintain a steadier flow.

These differences highlight how tree species influence not only rainfall interception but also how water is stored and released over time.

Looking Ahead: From Measurements to Modelling

To better understand what these findings mean at the scale of the whole Gradaščica catchment, Slovenian researchers are also working with hydrological models. The models developed by the University of Ljubljana and ARSO help explore how changes in land use – such as more or less forest, or different mixes of deciduous and coniferous trees – could affect water flow and flood risk in the future in the Gradaščica catchment.

Understanding these dynamics helps make smarter, more resilient choices when working with nature to reduce flood risks.